Freedom of Expression – The Bare Essentials

Freedom of expression consists of allowing people, in most circumstances, to perform expressive acts that others consider erroneous, dangerous, or appalling without suffering any formal punishment. The rationale underlying this freedom is that it is considered necessary for the emergence of truth, the proper functioning of democracy and the exercise of personal autonomy. As is the case with many freedoms, it is not an absolute one, but its limitations should be kept to a minimum and scrupulously justified.

Historical development

In early European history, suppression of free expression was in most cases deemed necessary for holding at bay two real or imaginary threats that bearers of secular and religious power feared. Established Christian churches thought they had to defend orthodoxy by suppressing heretical teachings. Princes had to protect their authority by gagging their political opponents.

Thus, to deal with the heretic and the dissident, a powerful and complicated system of censorship was developed which targeted dangerous publications and meted out severe punishments to those who were unwilling to abide by the existing guidelines. Obscene publications were also targeted as posing a danger to the morals of society, but until recently there was a wider consensus concerning their prohibition even among supporters of free speech.

It is not far from the truth to conceive the long and bitter struggles for freedom of expression from the seventeenth century and onwards as an endeavor to secure for everyone the right to express publicly his or hers religious, scientific, philosophical, artistic, and political views without fear of the authorities or public opinion.

The theoretical discourse produced along with the political and legal battles fought eventually succeeded in establishing freedom of expression as an entrenched right or liberty in various official documents, but free speech issues continue to occupy and divide scholars, lawgivers, and public opinion alike.

Three key purposes

Today it is widely agreed that freedom of expression serves three overarching normative purposes. First, it facilitates the search for truth in the fields in which it is relevant. As John Stuart Mill argued in “On Liberty” the free exchange of thoughts and opinions in a discursive context, irrespective of their epistemic value, contributes significantly to the formation of justified and true beliefs.

Second, it is essential for the proper functioning of democratic governance. Citizens need information from a variety of opposing sources to make reliable political decisions and, if elected officials are accountable to them, the criticism of those in power should not only be tolerated but encouraged. Third, it promotes personal autonomy envisaged as fulfilment of the plans we freely conceive and approve of. To be able to speak without fear is not only necessary for successfully engaging in a variety of trivial and everyday activities, but it can also be a powerful means for making our presence felt in this world and achieving self-realization to the extent that this is possible.

The freedom of expression and its exceptions

However, most disagreements arise when legitimate limitations are debated. These controversies become unavoidable, since it does not seem plausible to argue for absolute freedom of expression. A set of mostly unobjectionable exceptions concerns the place, time, and manner of expression.

Even if you agree with the content of a particular slogan, you do not want protesters to shout it outside your house at three o’clock in the morning. Furthermore, from a philosophical point of view, it seems reasonable to argue that at first sight certain forms of expression should be suppressed if they counteract the noble purposes that free expression is supposed to serve.

For instance, I have argued that the dissemination of fake political news during the pre-election period could be made illegal, since it confuses and manipulates voters. Along the same lines, it is claimed that the harsh convictions of journalists for libelling public officials may have a chilling effect on investigative journalism, a practice which is crucial for uncovering official misconduct.

Moreover, shouting falsely “Fire!” in a crowded theatre makes members of the audience lose self-control. Finally, from a legal point of view, it is notable that apart from freedom of expression there are other equally important constitutional rights and liberties and that its exercise should not result in the violation of any of them.

Perhaps ordinary citizens may understandably feel bewildered by all these complex scholarly debates. Nevertheless, it is important for all of us to realize that we merely pay lip service to freedom of expression if we want to suppress forms of speech that we regard as fallacious, unpleasant, or infuriating. If we take great pains to allow only what sounds pleasant to our ears, we might reintroduce, through the back door, forms of censorship and oppression that have taken an immense amount of time and effort to eliminate.

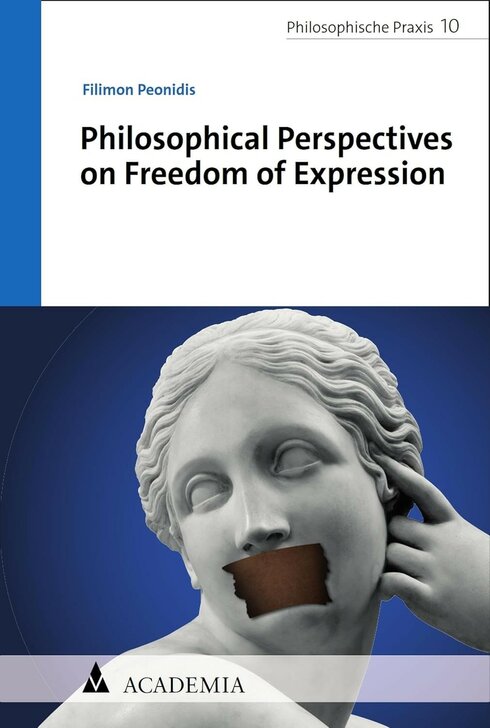

Filimon Peonidis has written extensively on moral theory, liberalism, freedom of expression, normative democratic theory and the history of democratic traditions. His most recent book in English is Philosophical Perspectives on Freedom of Expression (2024).

Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece

Director of the Philosophy Laboratory: Texts and Interpretations

(Foto: Photopress/Yannis Tsouflidis)